The Baldwin Styles

The Colour & Architecture of US Locomotives

By David Fletcher.

Introduction | Part 1: Origins | Part 2: Baroque Revival | Part 3: Development of Standards | Part 4: Case Studies

Part III: The Development of Standards at Baldwin.

The Baldwin builder's plate of the 1870s-1890s reads "Baldwin Locomotive Works Philadelphia, Burnham, Parry, Williams and Co." These were the names of the shareholding directors of the BLW during this time. Charles T Parry (1821-1887) began employment as a 15 yr old pattern maker's apprentice at the BLW during the mid 1830s, witness to the first years of locomotive construction under the direction of Matthias Baldwin. During the 1850s, with ever increasing demand for locomotives within the US, Baldwin Locomotive Works began to loose their market share to a growing list of new locomotive builders. Baldwin's market share during the 1840s had been in the order of 21% of all locomotives built in that decade in the US. In the decade of the 1850s, this share had dropped to 16%.

The locomotive building trade had evolved from the general workings of the horse-drawn carriage shops. Each locomotive built was individual; custom designed and built using the fabrication skills of the workmen on the shop floor. It was a slow process where parts were hand made and machined for as long as it took until the parts fitted together properly. The chief engineer provided only a basic guiding drawing as to the general arrangement of the locomotive and the overall size of its important parts; however complete and detailed drawings were generally not used. The detailed design of the locomotive componentry was done 'on the job' as it had always been, by the workmen who made the parts on the shop floor. There was little consistency in the process; however this is not to say that the locomotive builders of this age didn't build fine machines. Rather it shows the competence of the fabricators on the shop floor in carrying out the locomotive detail design as part of their normal duties. Charles Parry found this lack of system in the design and construction of locomotives inefficient.

Without massive expansion, BLW was unlikely to regain their market share in a growing world. During the 1850s through to the mid 1870s, Parry instituted a substantial change in the management strategies in the design and construction of locomotives, which also included the painting and decorative styles. The fundamental change was to move the management and control of the locomotive design away from the shop floor, to the drawing office. Parry mandated that all locomotive parts would be built from prescribed component drawings, and the drawing should be followed to exacting standards. If the part did not meet the required tolerances the first time, it would be discarded. Never again would parts be machined endlessly until they fitted, a colossal waste of man power and time. The fundamental changes involved the introduction of the following standards:

2 - The Book of Laws. - The Laws system was the realm of the design engineer. The Laws were the guiding design rules upon which all locomotive detailed drawings would be done. The Laws were only schematic design drawings in themselves, but covered all the governing design principles in locomotive components including important dimensions, important thickness, lap dimensions and selection of the right material to be used.

3 - The Book of Cards. - The Card system is the best known and important aspect of Baldwin's success. It is the development of highly detailed locomotive component drawings as a library of standard parts to be used on any locomotive. Locomotives were still custom designed, but detailed using these standardised loco component cards. Cards could only be drawn using the design rules provided via the book of Laws.

4 - The Book of Styles. - The Baldwin paint book which provided the numbered system for decorating locomotives to the Baldwin standards. In effect a Card system for decoration styles. The book was in colour and provided the governing rules upon which major locomotive components would be lined and decorated.

5 - The Finish Schedules. - A set of standards for the finishing of the various locomotive elements, noting whether a metal is 'Iron Finished' (polished Iron), painted metal, Brass, iron or wood, and includes the type of boiler jacket to be applied and boiler bands. The finishes standard is set up as a series of Letter groupings, A1, A2, D1, D2, and so on. I don't know what the upper end of the finishes grouping went to, however most of the locomotives of the 1870s I've been researching for exports tend to be in the D grouping. The specification sheet has a line item under 'Finish' and notes the finish code eg: 'D79', referring to the standard finishes sheets. Typically the finishes are already noted in the specification sheet as well.

In the simplest terms, the specification sheet identified all the specific requirements of a locomotive order; the Laws system instructs the design of the locomotive and its parts at a functional and performance level. The Laws instruct the Cards for the detailed drawing of the locomotive parts. The Book of Styles informs the paint shop on the required decoration of the locomotive. The locomotive's design and construction was entirely ruled via the use of drawings. The drawings were followed exactly and no deviation at the shop floor was tolerated. The only document that is specific to the actual locomotive ordered was the spec sheet; the Laws, Cards and Styles books were generic and used on all locomotives. Together, these formed a system which enabled a high level of Quality Assurance within the factory and enabled Baldwin to increase production with minimal physical expansion.

In many a case, nothing more than a spec sheet was needed for a new locomotive order. Often, the drawings required to build a new locomotive were already in the company's library of Cards. When new parts were needed and not found in the library, a new card would be created and added to the library, following a previously prescribed design Law. If the component was something completely new, a new Law would be created by the design engineers, and then a set of Cards would be created anew from that Law, often superseding earlier designs.

This complete system is regarded as one of the truly innovative manufacturing systems of the 19th century. Like all things founded on necessity, the Baldwin system was an adaptation of a similar concept used in the design and fabrication of fire arms in the US established in the early 1800's. The complete system enabled BLW to build locomotives by the hundreds on a yearly basis. Through the 1860s Baldwin's market share had increased from 16% to 24%. This rose to 32% in the 1870s and to 39% in the 1890s. What is more amazing is that not only had their market share increased, but they obtained that increase in the face of large increases in demand for locomotives on a global scale. In 1850 BLW built only 37 locomotives. In 1890 they had built 946 in a single year. In 1880 where most builders had clocked up locomotive numbers in the hundreds, Baldwin rolled out their 5000th locomotive, a stylish, high wheeled 'A' class 'single', 4-2-2 locomotive. The BLW drawing management system remained at the heart of the Baldwin Company until their closure in the 1950s, the largest builder of steam locomotives in the world.

The system also had the added benefit of being able to provide spare parts for repair anywhere in the world at short notice. The system was highlighted in the Baldwin catalogues of the 1870s. From the 1877 catalogue, Baldwin wrote the following:

"All work is accurately fitted to gauges and templates(sic) which are made from a system of standards kept exclusively for the purpose. Like parts will, therefore, fit accurately in all locomotives of the same class. This system of manufacture is a distinctive feature of these works. Its value and importance to the users of locomotives cannot be overestimated. By its means the expense of maintenance and repair is reduced to a minimum. A company whose railroad is equipped with our locomotives may save, almost wholly, all outlays for shops, machinery, drawings, and patterns for their repairs. The necessity of maintaining for the same purpose an organisation of skilled workmen at a constant expense is also obviated. Every important part of the locomotive being accurately made to a template, we can at any time supply a duplicate part, made to the same templet, which is sure to fit in the place of the original. The large number of locomotives at all times in progress, and embracing the principle classes, insures unusual and especial facilities for filling at once, or with the least possible delay, orders for such duplicate parts."

Baldwin Colour Schemes.

A typical Baldwin locomotive built for passenger service in the US in the early 1870s would be painted a deep wine colour across the entire locomotive. The wheels were Vermillion, an orange/red colour and major linework provided in gold, with red, cream , blue or green supporting linework. Contrasting colours would also be used on the wheels, tender and cab areas in the form of coloured bands and starbursts on the wheels. The sand box sides, cylinder sides and tender were decorated with arabesques. The decoration used by Baldwin in the 1870s became the basis for the first styles documented in the 'Book of Styles' in 1874.

|

| The restored Baldwin 2-6-0 'Empire' of 1873 is a good example of locomotive decoration of the early 1870s, the dark painted areas on the locomotive would have been painted a 'wine' colour. |

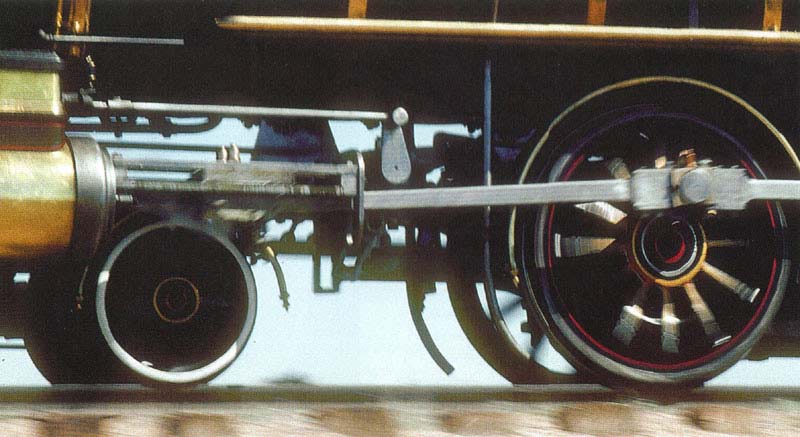

Red wheels gave way to painted wheels matching the base colour around 1874, further reducing the number of different colours applied to a locomotive. Red wheels had been a major component of locomotive decoration for 20 years in the US, was practiced by all builders, and unlike to the deep tones of the superstructure, did not really marry in with the Architectural colours schemes used in the Victorian building styles of the day. So what is it about the red wheels anyway? The particular shades of orange/red used were very bright and stood in stark contrast to the deep tones of the superstructure. In a world were speed and motion represented technological progress, the painting of the wheels in contrasting colours highlighted the wheels in motion - a literal celebration of their technology - speed and locomotion. From 1874 onward Baldwin used dark coloured wheels to match the colour of the locomotive superstructure. To highlight the motion of the wheels in contrast to the superstructure, Baldwin applied colourful decoration to the wheel spokes in a star, or 'starburst' pattern. The starburst design on the deep painted wheel colour produced an almost strobe like effect when the wheels were in motion, which again helped to celebrate the movement and speed.

|

| A Baldwin drive wheel with contrasting star burst on hub and spokes - The restored 1876 4-4-0 'Sonoma'. |

|

| A close up of a Builder's photo of the Style 1 wheel. |

|

| Style 1 wheels in motion on the 1875 restored 4-4-0, Eureka. |

Baldwin's Styles system was a robust and versatile card system for the striping and decorating of locomotive en masse. The book began with the documentation of existing styles dating sometimes to late 1860s and early 1870s. Baldwin's Style 1 was reserved for decorated passenger locomotives, the pride of the fleet, featuring ornate arabesque, brass dome wrappers and painted Ash, or polished walnut cabs. A good example of Style 1 is seen in the preserved NPC #12 'Sonoma' at the California State RR museum, and Dan Markoff's Eureka (both Lake & Gold, Style 1). A preserved example of a 'Wine & Gold, Style 1' locomotive is the Santa Cruz RR 'Jupiter', preserved at the Smithsonian Institute. Style 2 was a simpler lined tank engine style, while Style 3 was a robust working engine style of linework and decoration, with minimal polished brass and natural woodwork. Style 9 and 10 were road loco and tank loco styles based on the Pennsylvania RR livery from 1868. The locomotive 'Empire' V&T #13 at the CSRM, predates the book of styles, but would most closely resemble Baldwin's Style 27 including the Vermillion wheels.

In the late 1870s the 3 original styles were updated. The book of styles was an evolving document. Locomotives types originally painted to Style 1 generally became painted to the new look 'Style 49' and hard working freight locomotives style 3, became style 50. An excellent example of Style 50 is provided on the restored 1880 Baldwin 10-36-E 2-8-0 of the ATSF at the Kansas Museum of History in Topeka, Kansas. ATSF #132 is an example of Baldwin's 'Black & Color, Style 50', a very typical paint style for 2-8-0s in 1879/1880.

|

| ATSF #132, an 1880 2-8-0 in Black & Color, Style 50. |

Upon the closure of Baldwin in the 1950s, there were some 379 styles in the paint books. The book of styles was not a picture book of full locomotives in colour. Rather it illustrated the decoration of individual locomotive elements at a generic level and could be applied to any locomotive. Each locomotive element was provided with a reference number. Typically the elements were kept together within the book, such as 72 styles of locomotive drive wheel all shown together, page after page, numbered from 1 through to 72.

|

| Samples from the book of styles, note also specification sheet and builder's photo in the image, essential in reconstructing original locomotive styles today. |

There were pages full of painted and lined drawings of locomotive domes, locomotive cylinders, cabs, side and saddle tanks, and drawings for tender tanks. Different locomotive elements could be brought together to create a painting style number to be applied to a locomotive. From 1874 through to the end of Baldwin, the spec sheets noted the colour scheme and decoration for the locomotive referencing the book of styles.

|

| Example of the Baldwin 'Style 1' sand box and steam dome - note the arabesque of the dome sides and tops. These examples painted atop a 'Lake' base colour - the restored 1876 4-4-0 'Sonoma'. |

The lower section of a typical Baldwin specification sheet notes the colour scheme to be applied to a locomotive. As long as you can view the full Baldwin spec sheet for a locomotive built after 1874, you will find the necessary information needed to uncover the colour scheme. The spec sheet noted 3 important attributes regarding colour scheme - (1) the base colour to be applied to the locomotive, (2) the basis for the linework decoration colour, and (3) the style reference number. In addition to this, the spec sheet also notes the Finish Code, usually a single letter and number, which outlined metal finishes such as the boiler jacket material and boiler bands style, brass fitments and areas of polished or painted iron.

|

| An extract from a specification sheet indicating the colour and style of the specified locomotive. This example is take from an 1880 2-6-0 to be painted Olive Green and Gold, style 106. Note how the sheet formerly indicated 'Style 9', crossed out and replaced by 'Style 106'. Style 9 is a classic Pennsylvania RR livery, utilised on a number of railroads and used on export locomotives as well. This example was a narrow gauge mogul built for the South Australian Railways, painted in a livery to match a number of mainline locomotives built by Baldwin for that line - the mainline locomotives were painted Style 9. However when the narrow gauge engine was specified, the decorative wheels of Style 9 were probably too intense for the loco's tiny 38" drive wheels, and thus were painted in much plainer decorative style. Style 106 was the result - a locomotive that was identically painted to Style 9, but with simpler wheel decoration. |

2 - The Linework Base Colour - This is the 2nd colour noted in the spec sheet. It is usually listed as one of 3 colours:

- Gold = Metallic gold linework achieved usually via gold leaf or emulsions with metallic gold particles within the paint.

- Color = Linework basis to be gold paint, usually an imitation gold more akin to dark yellow than an actual metallic gold.

- Aluminium = Aluminium silver linework which gives the appearance of a locomotive lined in white.

3 - The Style Number.

This single style number refers to the book of styles and completes the decoration in terms of secondary colours, striping patterns, colours of decoration to be used. The single style number often relates to a number of different style numbers within the book itself.

The above colour scheme attributes would then be applied to the locomotive along with other Baldwin standards that were constant for all locomotives. Such standards include the black finish to the stack, smokebox and firebox, treated with a heat resistant mixture of lampblack, Linseed oil, plumbago, benzene, naphtha and other materials - not actually black paint. In the 1870s graphite was not used on the smokebox; however it became more common place by the turn of the century. Sometimes the smokebox was treated in black, while the smokebox door alone was graphite. Another standard was the use of hard wearing and cheap mineral paints in areas of high wear, not seen easily by the viewing public. The mineral paints were a dark brown/red colour, used on running board tops, cab roofs, tender tops and tool boxes, coal bunker sides and floors.

Boiler jackets were typically clad with planished Iron, a type of heat and pressure treated sheet iron, with a natural gun-metal grey lustre. Planished iron was applied without paint to the boiler, and left in natural state. It was both heat resistant and rust free. Planished Iron was used by Baldwin and most other US builders, and came from two locations. Originally Planished iron came from factories in the Urals in Russia, to become known as 'Russia Iron'. In the 1870s, with rising costs of the special imported material, Iron foundries in the US began to produce their own cheaper equivalent, to be known as 'American Iron'. Baldwin continued to use American Iron as standard well into the 20th century. Boiler bands were brass, painted iron or American iron. Russia Iron sheet metal was used in building construction, including roofing and chimney pipes. The US locomotive builders were not the only users of Planished iron. Builders in Scandinavia, Switzerland and Eastern Europe also jacketed their locomotives in this manner.

One final note about paints and finishes at Baldwin. The Book of Styles was a graphic book showing locomotive standard elements hand-painted in full colour and fully lined. The Master painters at the factory would use the Book of Styles as a guide when applying the various styles to the locomotive they were painting. Since locomotives came in many shapes and sizes, and the book of styles only shows a specific application of a style on a typical locomotive element; the painters would need to adapt the styles to suite the format of the engine they were painting. As such we see some variation in the way that these styles are applied, variations were caused by fitting a particular style onto a specific loco format, and variations were caused by different Master painter's interpretation of the style book within the factory. We also see changes in application over time due to stylistic trends. Often, specific style cards, such as domes and cylinders, developed in 1880 were still in use in the 1920s. The Style 16 dome developed in the 1880's, was still used after 1900, however the line-work to the base of the dome is deleted, while the horizontal bands of colour were still applied true to the original style. It is far easier for us today to obtain the specification sheet, get hold of the style cards and recreate the finishes on a locomotive by studying how these styles were applied by studying the builder's photo. Sometimes we are left scratching our heads when certain elements of a style seem to have been totally altered to suite the total look of an engine. Thus the painters still had some level of control in keeping the decorated engine visually balanced. This does not mean they deviated or painted the engine to their own preference or on a whim. The line-work and colours and setouts are pretty consistent with the style book. It was rather the need to adapt the style to fit a particular engine in terms of geometry and aesthetics that resulted in the changes we see. The Book (two volumes) survives today at the Special Collection at Stanford University Library. Slide copies of the Style book entries can be ordered from Stanford and the CSRM Library for the purposes of research.

Please use the navigation links below to continue to the next section.

Introduction | Part 1: Origins | Part 2: Baroque Revival | Part 3: Development of Standards | Part 4: Case Studies